Philip Harris Medical

Maggie arrives!

Philip Harris Medical’s Molly was delivered around the time Margaret Thatcher became Leader of the Opposition (1977?) so it was promptly named Maggie. Here indeed was an Iron Maiden, and painted blue. There were to be six VDUs (four for the telesales office) and two printers (one for directly printing invoices in the warehouse). After some weeks gestation while we developed the programs at Leicester and PHM checked them out very thoroughly and prepared themselves, LOS was born when PHM opened for business, "live" on Maggie on the first Monday of November in that year.

Anne McGrory and myself (Joe Templeman) were in attendance with Kath (Hodges), Mr Ruston (the MD) and other managers standing by behind the telesales girls as they began their calling rota. It was a revelation! No Molly had ever had the opportunity to show but a fraction of what it could do until that morning. I went through to watch Maggie. Yes, her lights were flickering. Instructions were being fetched and executed, for a real purpose now. Interrupts were being taken from all quarters and dismissed methodically. Drive belts were staying on and propelling the disc cartridges at the proper speed and the head access mechanisms were wild with frenzied yet directed activity. Power supplies were pumping energy at the correct voltages into the circuits. Down in the warehouse the printer was disgorging real invoices, the shelves were being picked of goods and the delivery vans were rolling. How long could it last? To me, every extra second was another million or so crash possibilities negotiated. There are advantages, in this situation, in not being aware of what could go wrong. So my frequent calls to Kath to "take a security" were cast aside until things quietened down at lunchtime. I could relax a bit after we’d secured the mornings work.

As other companies were to discover in their turn, the whole atmosphere of the business was transformed the instant their Molly went into action. It was there to help, not to intimidate. This atmosphere was subtle but tangible whenever I entered a building containing a LOS Molly. Mind you, a certain tool distributor did keep their entire stock of sledgehammers just outside the door to their Molly - just in case?

A significant component missing from LOS on that first day was any means to deal with a paper wreck at the invoice printer. This was because I didn’t have a clue how the situation could be handled, until it happened. That occurred soon enough, and the document reprinting utility was soon operational.

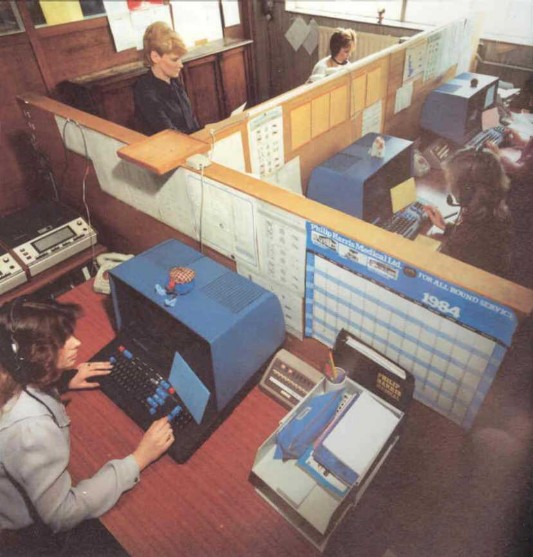

Maggie and Denis in 1990

By 1990 Maggie was bulging with the maximum 64K words of memory and the interfaces to serve 17 VDUs and 5 printers, and now backed up by a second Molecular (named Denis, after Mr Thatcher). Even though the processor still ran at the same speed as in 1976, no realistic UNIX alternative could yet match the performance of the machine code applications software. However, hardware breakdowns were a constant anxiety which Denis could only partially mitigate, so a reliable UNIX alternative was being sought. It became a close race as to which of the two Maggies would outlast the other in office. In the end, Maggie the Molecular had a narrowly longer run.

Though Maggie's electronic circuits remained 1970s technology, and her on-line storage capacity never rose above the original 13 megabytes, the emergence of microcomputers (followed by Personal Computers or PCs) in the 1980s provided her a lifeline to capabilities she could not hope to offer unaided. Plugging one of these into her in place of a "dumb" VDU enabled her to transfer data with the emerging networks, to download to high-capacity archival storage, and even gave her an accurate clock.

Joe Templeman

Kath's reflections on "Maggie the marvelous computer"

As some of you [at Philip Harris] know we have just purchased yet another state of the art computer, to cope with our rapidly expanding business. This one, extremely powerful and with massive amounts of disc space and memory, is a far cry from Maggie, our very first in-house computer.

When I joined the medical company it had no computer, in fact very few businesses owned one in those days. Computer bureaus were the big things then and a bureau ran our very first system. Orders were handwritten, picked and then the dockets sent back upstairs to be connected to punch tape which was sent off each Friday evening to Mills of Monmouth, who then returned it to us on Monday morning as invoices. This may seem primitive now, but for Philip Harris Medical it was a giant leap forward as until then all invoices were typed, pricing was done by means of metal plates and a Bradmar System and they were then "comped up". This was a laborious task and work was always late, copy invoices had to be then sent to head office for statements to be produced, these always went out at least one month late and it was often two. All credit notes were hand-written in immaculate copperplate by a gentleman called Pryce Jones and as you can imagine it could be a few weeks before a customer received his credit note. (Now they want them yesterday!). The bureau system was such an improvement on all this that Mr Ruston, who was then our managing director and Mr Linney, who was sales director, decided to buy a computer of our own and the hunt was on. After many site visits and much discussion we decided on a BCL Molecular and Maggie was born.

She consisted of a large metal box with a row of switches topped by twinkling lights and two large disc drives which each had a fixed and top-loading removable disc. The whole thing was painted true Tory blue and as this machine had a mind of its own and the Russians had just christened Mrs Thatcher the "Iron Lady" its name just had to be Maggie. The box contained only 40k of memory to start with the rest were filled with air! The disc drives each had one 3.5meg fixed disc and one 3.5meg removable disc, unbelievable these days when even the smallest laptop has much more than this. The person in charge of designing the system was Chris Green, then of BCL, now our chief programmer and well known to many of you. The operating system and most of the programs were written by Joe Templeman, who you also see around from time to time, as he designed and wrote our Worm system and also our Alpha I ordering system. Maggie's programs were all written in machine code, which made her response times very fast indeed and the disc drives were using a very modern concept of mirroring, designed by Joe, which meant that in the event of a drive failure, (and we had many) the faulty one could be taken out of the system and we could continue working on the other.

Although Maggie was marvelous and the business began to expand it was not all plain sailing. Computers in those days were not as reliable as their modern counterparts and Maggie was very susceptible to "blips" in the power supply and also to static, quite a bit generated by VDU operators who wore nylon underwear! Static would lock all the VDUs and Joe wrote a special program called "kick" which I typed in to start them all off again. Far more serious was a sudden surge or drop in the power supply, which could stop the processor.

The row of lights above the switches was a clear indicator of Maggie's health and if they were all twinkling merrily she was happy and working. I used to dread the moment when there was a cry from the sales office, then from upstairs to say that they had all stopped and on dashing into the computer room I would find that the lights had stopped twinkling and had changed their pattern. The first move was to "bootstrap" the processor, using the switches this was quite a complicated procedure and if you got one of the steps wrong you had to go back to the beginning and start again. I used to press the "start" switch at the end holding my breath and praying that it would. If it didn't, I then had to call a programmer and he would attempt to correct the fault, if this proved impossible I then had to call the engineers, while the computer was down we had to return to manual working, and all orders had to be coded with bin numbers taken from the print outs, a laborious task. They were then sent down to the warehouse by means of Lamson-Paragon tubes, which were a series of large metal pipes running around the building and glass document carriers which held the orders. They were then placed in the tubes and sent round the warehouse by compressed air. This worked fine until a carrier would get stuck somewhere on its journey and then all hell was let loose. We had to have a "runner" who would tear up and down the stairs with the orders and although one no-one actually dropped dead while acting as runner it was a close run thing once or twice!

As the business expanded the effect of a breakdown became more and more horrendous. We purchased another smaller Molecular as back up for Maggie, which was housed downstairs in what is now the visitor's toilet. We copied Maggie's data onto the two security discs at 1 o'clock and 5 o'clock and these were carried down and copied onto the back-up, christened Dennis, by means of a patch panel on the wall and a set of cables and plugs. Although this enabled us to carry on working it created problems of its own, as Dennis was only valid up to the last security and if Maggie decided to throw a wobbly at about 12.30 which she invariably did, it meant that a whole morning's work had disappeared down a black hole! A small team of people would determine what the first and last invoice numbers were (after security and pre-Dennis) and then run round the warehouse finding them all and putting them into number order, ready for re-entry when Maggie was up and running again. This also applied to credit notes, cash postings, stock adjusts, goods loaded and purchase invoice postings, all had to be done again once the computer was up and running. Maggie also had a nasty habit of breaking down just after stocktaking, screwing up the newly counted and adjusted stock figures, which didn't exactly make her popular with the auditors. On one classic occasion we had three breakdowns in the first week after stocktake and had to do it again the following month. Because we were so busy and the business was so dependant on the computer to get the work out on time, when Maggie broke down there was a constant stream of people in and out of the computer room asking how long it would be out of action and how the engineers were getting on which didn't exactly please them, and as one or two of them burned on rather a short fuse I used to try and shoo everyone out of the room as quickly as possible. I'm sure that the engineers dreaded a call from us as much as I dreaded having to make one.

In spite of Maggie's temperamental nature she lasted for fourteen years and BCL used us as a showcase selling many systems based on ours. When the time came to replace her we found that it was impossible to equal her response time with a modern system, although of course they were much more reliable and could offer much more in the way of programs. Our present system has been re-written many times to accommodate our expanding business but it was Maggie that started it all. Thanks to the foresight of Mr Ruston and Mr Linney in choosing a system so far ahead of its time, Philip Harris Medical was dragged kicking and screaming into the 20th century and has never looked back.

Kath Hodges (Stirchley) c1995